San Luis Reservoir image via Google Earth

Written by Edward Smith

Another zero to near-zero allocation of water means even fewer options for growers in the Central Valley as plans to comply with new state regulations roll out.

Despite significant rainfall in October and December, the Bureau of Reclamation announced Wednesday a 0% surface-water allocation for South-of-Delta users who draw from the Central Valley Project (CVP), which includes the Westlands Water District. For growers in the east side of the Central Valley who get their water from the Friant-Kern Canal, they received a 15% allocation.

“We began the 2022 water year with low CVP reservoir storage and some weather whiplash, starting with a record day of Sacramento rainfall in October and snow-packed December storms to a very dry January and February, which are on pace to be the driest on record,” said Ernest Conant, regional director for the Bureau, in a new release. “Further, the December storms disproportionately played out this year in the headwaters—heavy in the American River Basin and unfortunately light in the upper Sacramento River Basin, which feeds into Shasta Reservoir, the cornerstone of the CVP.”

The Central Valley Project is a federally constructed conveyance system that brings water from the Shasta Reservoir to as far south as Bakersfield and the Tehachapi Mountains.

Ryan Ferguson who operates Ferguson Farming near Huron said the announcement is pretty disappointing, especially after the wet December and October from last year.

“Coming off December I was optimistic we would be able to fill a lot of the reservoirs,” Ferguson said.

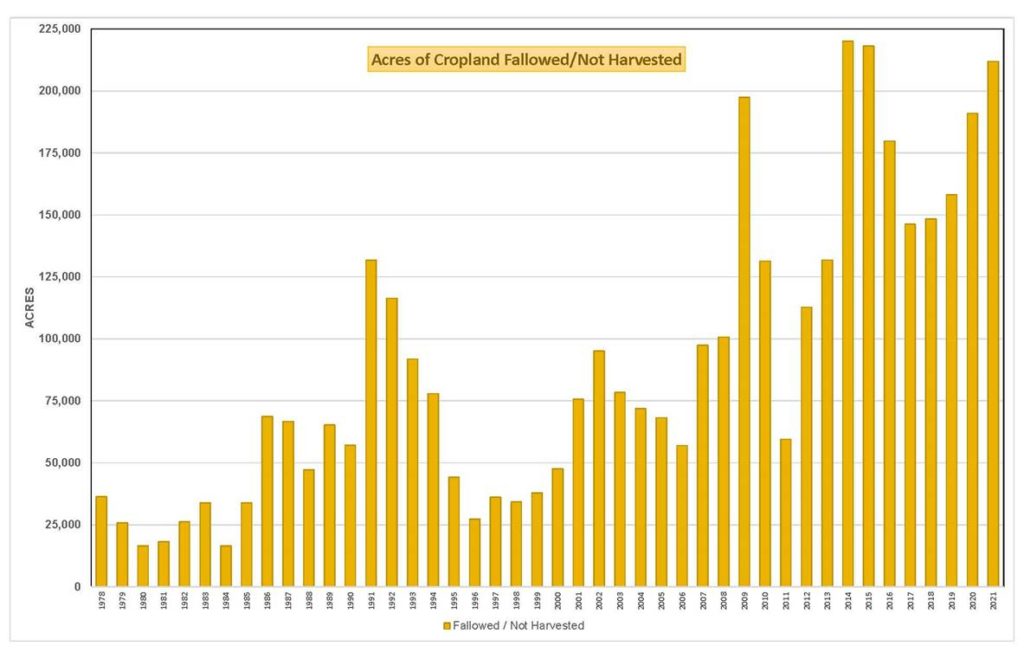

He’s going to be fallowing nearly 40% of the 3,000 acres he farms, eliminating all of his cotton and nearly all of his tomatoes.

And he’s not the only grower eliminating row crops. Tomatoes, garlic and onions are all suffering, Ferguson said. And acreage for lettuce in the spring and fall has shrunk dramatically, which will affect food prices, he said.

Growers are even removing nut orchards to balance their water usage. A 15-year-old orchard might be transitioned out when the typical lifespan is 25 years.

He has $1 million worth of supplemental water carried over from last year he’s going to dedicate to irrigating his orchards.

Growers don’t like to water almond trees with ground supply because trees don’t react well to salinity, but Ferguson said there’s no way around that this year.

Almond prices can’t support water costs going up much more. In 2021, water prices neared $3,000 an acre foot.

Growers are still having difficulty accessing foreign markets with shipping disruptions as well, which could potentially impact prices as domestic markets alone can’t bear the supply grown in the region.

In previous years, Westlands growers have turned to the four water districts in the San Joaquin River Exchange Contractors to sell excess water.

But they’ve received a “critical year” designation. While there is the ability for smaller levels of transfers to happen, in critical years, those transfers become very limited, said Cannon Michael, a grower and board member for the San Luis Canal Company.

This is the first year Westlands Water District has implemented a district-wide pumping cap of 1.3 acre-feet of water per acre as part of the state-mandated groundwater sustainability plan.

Ferguson said this year’s cap is an aggregate cap. Groundwater usage of 1.3 acre-feet extends across the entire district, meaning neighbors can use more or less as long as there’s a balance.

Next year is the first year the cap applies to each individual irrigator.

Over the next eight years, groundwater pumping will be reduced to as low as .6 acre-feet of water.

In the eastern Central Valley, contractors with the Friant Water Authority received a 15% allocation or 120,000 acre feet for water users with a Class I contract. Officials with Friant Water estimate that as much as 240,000 acre feet could be made available based on current snowpack levels and reservoir conditions at Millerton Lake.

This is the fourth year in the past decade South-of-Delta users such as Westlands Water District have received a 0% surface-water allocation, making it harder to replenish aquifers. And as state water laws get progressively more demanding, it’s becoming more difficult to meet the requirement of drawing out only as much water as is put in.

“Growers in Westlands are going to be making difficult decisions,” Ferguson said.