The Savory Basin outside of Fresno was built two years ago to refill the aquifer with captured stormwater. The Fresno district spent millions to buy farmland and create basins for percolating water underground to help meet the requirements of state groundwater management regulations. Photo by Larry Valenzuela, CalMatters/CatchLight Local

Written by Alastair Bland with CalMatters

The powerful storms that clobbered California for weeks in December and January dropped trillions of gallons of water, flooding many communities and farms. But throughout the state, the rains have done little to nourish the underground supplies that are critical sources of California’s drinking water.

Thousands of people in the San Joaquin Valley have seen their wells go dry after years of prolonged drought and overpumping of aquifers. And a two-week deluge — or even a wet winter — will not bring them relief.

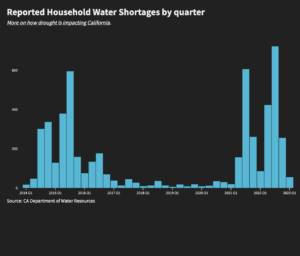

Even in January, as California’s rivers flooded thousands of acres, state officials received reports of more than 30 well outages, adding to more than 5,000 dry residential wells reported statewide in the past decade.

“Just one wet year is nowhere near large enough to refill the amount of groundwater storage that we’ve lost, say, over the last 10 years or more,” said Jeanine Jones, a drought manager with the state Department of Water Resources.

Water from heavy rains can reach shallow groundwater basins in a matter of days, but in places where wells must pump from deep underground aquifers — like those in the San Joaquin Valley — this can take months. And even a season’s worth of storms is not usually enough to restore wells left high and dry by years of overdraft.

Restoring California’s groundwater is not as simple as waiting for rain and letting it seep into the ground. It requires detailed planning and scientific analysis of project sites, and uses tens of millions of dollars in state funds. Land has to be purchased or growers must be compensated for flooding their fields. And it also means that growers — and to a lesser extent, communities — must reduce the water they pump.

Graham Fogg, a UC Davis professor of hydrogeology, said the recent rainfall could substantially help minimally impacted areas, like much of the Sacramento basin, where groundwater tables are only 25 to 30 feet down. But it’s a far different story in the San Joaquin Valley, where the water table is 100 to 300 feet down, even 700 feet in some places.

“That’s where most of the dried-up wells have occurred,” Fogg said, “and that’s where it will take years, maybe decades, of not only managed aquifer recharge, but also reduced pumping from wells, to raise groundwater levels back to more appropriate elevations.”

According to state officials and other groundwater experts, most wells in the San Joaquin Valley have virtually no chance of recovering unless groundwater pumping is drastically curbed.

“I’ve seen about 2,000 wells go dry, and we don’t see wells recover on their own,” said Tami McVay, director of emergency services for Self-Help Enterprises, a San Joaquin Valley nonprofit that provides funding to residents who need new wells. “They sometimes recover for a couple of days, but then they go dry again.”

Groundwater is liquid gold

Groundwater is among California’s most precious natural resources, providing about 40% of the water consumed in most years. It is an inexpensive, local source in a state where many cities rely on imported water and rural towns have no other sources. And its importance is magnified in dry years, when reservoirs fed by rivers are depleted.

The San Joaquin Valley’s groundwater reserves have been relentlessly pumped by farmers for decades. Tens of millions of acre-feet have been pumped from the ground, causing the water table to steadily drop and thousands of wells to go dry.

A handful of communities, largely home to low-income Latino residents, have run out of water, forcing people to use bottled water for everything. The true scope of the problem, in fact, may be underestimated, since many dewatered wells are unreported.

East Porterville, Tooleville, Tombstone Territory, Fairmead, Lanare and Riverdale are just a few of the San Joaquin Valley communities that have been hit hard with dry wells.

“There’s so much political pressure to maintain the status quo, and to continue pumping, because it’s tied up with economic profits. And the end result is community members who can’t rely on their wells for safe water,” said Tien Tran, a policy advocate with the group Community Water Center, which advocates for water equity.

Almost a decade ago, California enacted a law that is supposed to protect groundwater reserves from overpumping. The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act requires local groundwater agencies to halt long-term depletion and achieve sustainability, defined by specific criteria. But the deadlines are almost 20 years away, and basins are still being overdrafted.

The San Joaquin Valley’s major groundwater basins are designated critically overdrafted by the California Department of Water Resources. A year ago, the agency rejected the region’s groundwater sustainability plans on the grounds that they inadequately considered the needs of residential wells, among other impacts.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s water strategy released last August called for increasing groundwater recharge by an average of half a million acre-feet each year. On Jan. 13, state water agencies announced a program to expedite approval of recharge projects.

Department of Water Resources Director Karla Nemeth said the voluminous mountain snowpack dumped in January offers a prime opportunity, and a time-sensitive one, to recharge aquifers.

“We’ve got a heck of a lot of snow in the Central Sierra,” she said. “That snow is going to melt, and we want the local water districts to be positioned to capture some of that excess snowmelt and get it underground.”

The quest to store rainwater underground

Compelled in part by state law, and often supported by millions in state funds, some farmers and other land managers have dug large recharge basins to capture stormwater and allow it to sink. Cities design similar projects, and in recent months alone, they’ve put tens of thousands of acre-feet of water into underground storage.

While not enough on their own to reverse overdraft, these programs could serve as models for scaling up recharge efforts statewide.

In the Tulare Irrigation District, for instance, stormwater during high flows is diverted into 1,300 acres of ponds used to recharge groundwater. In addition, in a new program launched last year, farmers who sink water into their fields during storms can get it back later, during dry periods. General Manager Aaron Fukuda said it has motivated dozens of landowners to take part this winter. As of Feb. 3, the district was bringing in water at a rate of 1,500 acre-feet daily, mostly to be deposited in the ground.

“The actions our district took last year are paying dividends this year,” Fukuda said.

About 40 miles to the north, the Fresno Irrigation District has captured at least 9,000 acre-feet of water since December, according to Kassy Chauhan, executive director of the North Kings Groundwater Sustainability Agency, which manages the district’s groundwater.

Much of this water was diverted into some 900 acres of basins, including 180 acres that were recently constructed. The Fresno district spent millions buying former farmland and forming these basins, which are basically bulldozed depressions ringed by earthen berms made for the express purpose of depositing water underground.

“We were able to capture that water in those basins,” Chauhan said. “It was clear progress.”

Another example of a recharge project is the Pajaro River Valley, on the Central Coast. The local water agency has collaborated with researchers to identify potential recharge hotspots and carve out infiltration basins. One has been in operation for 20 years, and more are coming. The goal, said Brian Lockwood, general manager of the Pajaro Valley Water Management Agency, is to enroll farmers in a rebate program that pays them for flooding their land.

But these types of efforts, even applied broadly, will only have a limited impact. Managed aquifer recharge using local water could potentially recover just 3% to 8% of the San Joaquin Valley’s groundwater overdraft, according to 2020 research.

UC Davis Professor of civil and environmental engineering Jay Lund said, while he endorses groundwater recharge projects, there is a better way to lessen the Central Valley’s water woes.

“We have to reduce demand,” he said.

The problem is that farmers are still pumping water out of the ground faster than it’s going back in.

Experts have predicted that the state groundwater law could eventually force as many as 750,000 acres of farmland out of production, permanently easing demands on the state’s water supply.

Groundwater agencies tend to “emphasize solutions on the supply side, and relatively little on the demand side … and the supply numbers do not add up,” according to a 2020 PPIC analysis.

In much of the Tulare Irrigation District, the groundwater table sits at a record low elevation of 180 feet underground, and Fukuda said the district’s sustainability plan — required by the state’s groundwater law and developed by the Mid-Kaweah Groundwater Sustainability Agency — allows for the water table to dip a bit farther before leveling off. The North Kings agency, according to Chauhan, is also allowing some continued decline.

According to data from more than 1,200 San Joaquin Valley monitoring wells, the water table has been dropping for at least two decades, in many places more than 2.5 feet per year on average.

The groundwater plans that the state rejected last year were revised and resubmitted in July, and the state is expected to announce their next round of San Joaquin Valley assessments within two months.

Water equity activists who have studied the revised plans say they’re not impressed by the changes made.

“We still found that these plans are not taking adequate steps to protect drinking water users in the basins,” said Nataly Escobeda Garcia, policy coordinator for Water Programs with the NGO Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability. “We anticipate that numerous domestic wells and public water systems will still be at risk of dewatering.”

The Community Water Center has predicted that almost 500 domestic wells that draw from the Kaweah Subbasin, in the southeast San Joaquin Valley, could go dry under the new plans.

“Domestic wells are disproportionately impacted,” Tran said. Tulare County alone has seen 1,810 wells go dry since 2014, according to the state reporting system. All but two were labeled “household.”

Replenishing groundwater has limits

With or without human intervention, water sinks into the Earth. Natural, or passive, recharge is the process by which hundreds of millions of acre-feet of water have accumulated in California’s shallow basins and deep aquifers. Recent research from NASA found that as much as 4 million acre-feet yearly may seep beneath the Central Valley.

But this doesn’t necessarily make a big difference. While the water can generate quick spurts of rebound of the water table, these post-rain gains — at least in the San Joaquin Valley — tend to be erased, plus some, by subsequent dry spells and continued pumping.

The result is a one-step-up-two-steps-down trajectory of groundwater decline.

“Overall water levels have been dropping and until it’s reversed, we’re going to keep getting dry wells,” Fogg said.

Even extremely wet periods have had only temporary benefits in the San Joaquin Valley. After the record wet 2017 winter, the water table jumped — in some places dramatically — but quickly dropped again, continuing the decline. Today more than half of the monitoring wells in Tulare County are at all-time low water levels.

Active recharge programs generated about 6.5 million acre-feet in the San Joaquin Valley alone in 2017, according to a eport by the Public Policy Institute of California.

“We have lots of active recharge already,” said Ellen Hanak, vice-president and director of the institute’s Water Policy Center. “The question is, with (the groundwater law), can we up our game?”

Paul Gosselin, the Department of Water Resources’ deputy director of sustainable groundwater management, said 42 recharge projects underway with $68 million in state support could add 117,000 acre-feet of water storage to the state’s aquifers — a big step toward meeting the governor’s half-million acre-foot goal. He said the department has $250 million available to support more recharge work.

Changing climate makes this work all the more urgent. The state’s system of capturing and storing water in reservoirs was designed in part around snowpack in the Sierra Nevada. But as the climate warms, mountain snowpack is becoming scarcer. It is melting faster and earlier, and more precipitation is falling as rain in the first place.

California’s existing reservoirs don’t have the capacity to store so much liquid water at once, but its aquifers do.

“Groundwater recharge will be a good way to compensate for that change,” Hanak said. But, she said, “there is a major time constraint — you’ve got to be able to get that water out there fast, because it’s coming down fast.”

Randy Fiorini, a Merced County farmer and former chair of the Delta Stewardship Council, thinks the slow pace of aquifer percolation is an obstacle that can only be addressed by building small holding reservoirs to capture stormwater.

“From there, you would meter it into a groundwater basin,” he said.

Urban success stories

In urban areas, maintaining groundwater is easier than in farm communities. But it takes active management.

The Orange County Water District provides water for the 2.5 million people who live in the northern half of the county. Despite minimal rainfall, it has relatively little reliance on imported supplies and uses a unique groundwater storage system.

A third of its water comes from the Santa Ana River, which originates in the San Bernardino Mountains and flows through San Bernardino and Riverside counties. The Inland Empire discharges voluminous amounts of treated wastewater into the river as it flows into Orange County, where it is deposited into ponds that recharge the aquifer, according to Roy Herndon, the district’s chief hydrogeologist.

Another third comes from natural rainfall plus imported Colorado River water. The rest is wastewater that is used to refill the aquifer after undergoing treatment so advanced that it meets or exceeds all drinking water standards, making it “essentially potable,” Herndon said. Built 15 years ago, the plant can produce 130 million gallons per day, enough water for about 400,000 households.

All told, the Orange County Water District has 1,100 acres of recharge basins which collectively absorb an average of 250,000 acre-feet of stormwater and runoff annually.

In Sonoma County, the local water agency is using a $6.9 million state grant to inject surplus water from the Russian River hundreds of feet underground. The project could enter its initial pilot phase next winter and eventually produce 500 acre-feet of water each year. If successful, other similar projects could follow, he said.

In 2018, Los Angeles County voters passed Measure W, which created a new tax on the owners of impermeable surfaces that direct water into storm drains leading to the ocean. Each year since its introduction, the tax has generated about $280 million in funds for use in supporting stormwater projects.

Since October, the county has captured more than 143,000 acre feet of stormwater in reservoirs and groundwater basins, according to Lisette Guzman, a public information officer with Los Angeles County Public Works. That’s enough water, she said, to support more than a million residents for a year.

Lund says the physical limitations of moving and handling surface water mean groundwater recharge projects cannot fix most of the state’s well problems.

“No matter how much (recharge) you do, you aren’t going to get more than 15% of the groundwater overdraft in the San Joaquin Valley,” Lund said. “That’s good, and you should do as much as you can economically, but you still have 80, 90% of the problem left.”

Gosselin, at the state water agency, is more optimistic, citing the new research, laws, funding and priorities in managing groundwater.

In the novel “East of Eden,” John Steinbeck described Californians’ tendency to forget about wet times when it’s dry and drought when it rained. But Gosselin said growers and water agencies are now planning ahead, rain or shine, to capture and store water in the ground.

“We need resiliency from climate change,” he said, “…and I don’t think people are going to forget about either right now,” he said.