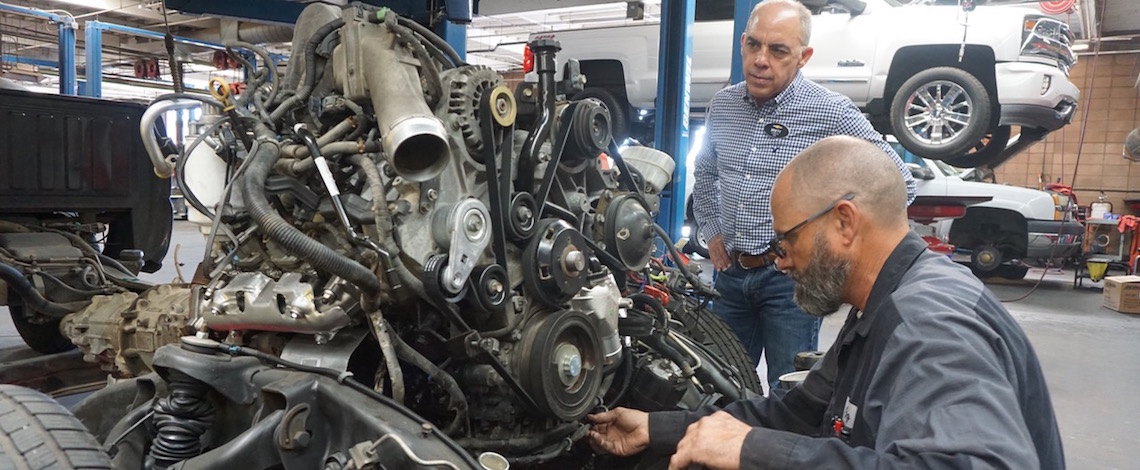

Brett Hedrick, owner of Hedrick’s Chevrolet in Clovis, looks on as technician Greg Elrod checks out an engine. Hedrick believes auto dealers should have had some input into a recent decision to ban gas-powered cars in California. Photo by Edward Smith

Written by Edward Smith

What appears to be the death knell for gasoline-powered cars in California has many new car dealers worried the infrastructure, logistics and product availability needed to support the change to zero-emissions vehicles may not be achievable in a 15-year timeline.

In an effort to curb emissions and climate change, Gov. Gavin Newsom in September signed an executive order directing the California Air Resources Board to develop regulations mandating the 2 million new cars sold annually in California be zero-emission vehicles by 2035.

“In a state that’s already not considered business friendly, this comes as another slap in the face,” said Brett Hedrick, owner of Hedrick’s Chevrolet in Clovis.

Hedrick found out about the announcement on the news.

“As a business owner, I don’t like being told what I cannot purchase,” he said. “As a consumer, I don’t like being told that either.”

Many car dealers feel they were left out of the conversation, given how keyed in they are to the needs of consumers.

Hedrick sells 17 different models of cars ranging from sedans to SUVS to pickups. Hedrick said the variety of electric vehicles on the market hasn’t caught up yet. In California, cars make up 45% of vehicles sold. The rest are crossovers, SUVs, pickups and vans.

“If I have a family come in that needs an eight-passenger vehicle, that’s one model. If I have a customer that comes in and they want the small, economic, commuter-car, that’s another model,” said Hedrick.

The order comes as manufacturers have been reeling from factory shutdowns during the pandemic.

Before the pandemic hit, consulting firm McKinsey & Company predicted that 400 new electric-vehicle models would enter the market by 2023.

In the months following economic shutdowns however, sales of new cars dropped sharply though, according to the Center for Automotive Research. The research organization in June said it would be a “complex undertaking” with tremendous capital requirements to restart production.

Consumers need cars for a variety of reasons, from long distance commutes to hauling heavy loads to outdoor venturing. Hilary Haron with Haron Jaguar Land Rover in Fresno fears the buying power of the Bay Area and Los Angeles basin would drown out the needs of consumers in the Central Valley.

“What the consumer wants and what legislators want don’t align,” said Haron.

Getting new cars to replace ones sold has been spotty, Haron said, though she sees October and November as the manufacturers’ chance to catch up with demand.

Of the 2 million new cars sold in California, 7% are electric.

Over the past few years, the demand for electric cars has risen significantly. For each year from 2015 to 2018, demand for electric vehicles nationally increased an average of 46%, according to a report from McKinsey & Company. But one major barrier has been cost. The lowest price electric vehicle is from Fiat, starting at $30,000.

Environmental advocates tout economic models that show electric vehicles can achieve price parity with conventional vehicles around 2025, according to a 2019 white paper by the International Council on Clean Transportation, but not without incentives to overcome “substantial market barriers.”

In his address announcing the ban, Gov. Newsom cited California’s consuming power as a way to drive technology forward making electric vehicles more affordable.

Of all new cars sold nationally, 12% are sold in California. That means one in every eight cars is sold in the state, said Brian Maas, president of the California New Car Dealers Association.

Driving the cost upward is the price of batteries. Manufacturers have had 120 years to perfect the internal combustion engine, allowing efficiency to lower cost. The electric market has had 30 years.

Also driving up cost are materials such as lithium or cobalt. A transition from below 10% market share for electric vehicles to 100% by 2035 means a spike in demand that could counter any technological advances to reduce cost.

Another obstacle to the transition is the availability of chargers. Cities were developed largely with gas-powered cars in mind. Across the state there are 15,057 gasoline stations, while there are only 5,060 electric charging stations, according to the Auto Alliance.

Not all of those chargers are the same. “Having a bunch of home chargers available isn’t the same as having a gas stations available at every freeway exit,” said Maas.

Filling up a car takes five minutes, but even the fastest chargers still take 20-30 minutes to fill a car. And most chargers aren’t the top-of-the-line ones, said Maas. The cost for a charger can be tens of thousands of dollars depending on charging capacity. If a charger isn’t a fast charger, it can take hours to fill a vehicle — not to mention the recurring threat of rolling blackouts.

“What does that look like with millions of electric cars trying to pull from that same energy?” Haron said.

Drivers have to know there’s a charger available at the end of their destination or risk being stuck on the side of the road. Using amenities such as a heater also drain electricity.

“All these technologies have to be improved so consumers feel, ‘you know what, I’m ready to make the switch,’” said Maas.

At the end of day, those in the auto industry want to be included in the decision-making. Car dealers such as Haron and Hedrick feel they were left out of the conversation that changed laws affecting their industries.

“Fifteen years is a little bit aggressive,” Haron said. “If you want to make a substantive change, you have to engage the people who know the industry, who know the science, who know how to get there.”